You Can’t Subsidize Your Way to Social Mobility

Families deserve more from policymakers than tax credits and bonds

This post is a repost from Upward Bound

Sen. Rev. Raphael Warnock (D-GA) and Sen. Michael Bennet (D-CO) offered yet another proposal to expand the Child Tax Credit last week. The Warnock-Bennet plan joins a long list of proposals to expand the credit, all of which would do little to actually improve child poverty and family welfare.

The child tax credit (CTC) currently provides up to $2,000 per child to offset the costs of raising a family. The American Rescue Plan (ARP) of 2021 expanded the credit by increasing the value of the minimum credit, eliminating the earnings requirement, and providing the credit to families who had lost jobs during the pandemic. The Warnock-Bennet plan goes further – their proposal would raise the maximum credit to $4,320 for children under 6 and to $3,600 for children 6-17 while also making it entirely refundable. It would also create a $2,400 “baby bonus” for newborn babies.

Proponents of expanding the CTC argue that family life is fundamentally unaffordable and that in order to meet need, families need more income transfers. Related, many proponents argue that fertility rates are below replacement because family life is so unaffordable. Expanding government subsidies for families would, in their view, meaningfully increase fertility.

Reducing child poverty is undeniably a worthy goal and policymakers are right to prioritize it. But expanding the CTC is a tried and tired policy that has done little to improve child poverty rates. Expanding the credit is also politically expedient – instead of doing the hard work to discover why family life is so expensive, it’s easier to just throw money at families and hope that it will lead to social mobility.

Families deserve better policies and more creativity from legislators than what one of the inventors of the credit described as a “failed experiment.”

Reducing Poverty Requires Work

Proponents of the Covid-era expansion argue that it will benefit 16 million children and lift a potential 400,000 children above the poverty line. All this translates to a reduction in child poverty by more than 40%. No studies have been done for the Warnock-Bennet plan. The Covid-era expansion was indeed successful at reducing child poverty in the short term, but there is little evidence to indicate that a permanent expansion would do much to keep children out of poverty in the long term. Making the expansion permanent would reduce the incentive for parents to work and marry which has long term consequences for social mobility. As American Enterprise Institute economist Scott Winship pointed out in the New York Times:

“But among those families with the weakest attachment to stable work and family life, it would be likely to consign them to more entrenched multigenerational poverty by further disconnecting them from those institutions.”

The current structure of the CTC incentivizes work by adding a 15-cent subsidy to each additional dollar earned until the maximum credit is reached. This offsets some of the “income effect” that allows a worker to meet their material needs without working. These earned income requirements are why the CTC is not considered an anti-poverty program. Goldin and Michelmore 2021 found that 87% of filers in the bottom 10% of the income distribution are ineligible for the CTC and the majority of filers in the bottom 30% are only eligible for the partial credit.

Removing the “work requirement” from the CTC – like the Warnock-Bennet plan would do – has real behavioral effects. Corinth et al. 2021 found that the removal of the earned income requirement would push nearly 1.5 million workers – almost 2.6% of all working parents – out of the labor force, with the greatest effect on single-parent households. This decline in employment and the associated loss in earnings means that child poverty would not fall as substantially as originally estimated. The authors find that, when behavioral effects are taken into account, the net effect of expanding the CTC would reduce overall child poverty by 22% – much lower than the commonly cited 40% projection – but would have no effect on deep poverty (50% of the poverty line).

Disincentivizing parents from working has very real consequences for social mobility. Increasing employment from 20 to 30 weeks out of the year raises the chance that someone will rise above the poverty line by 16% and reduces the likelihood that someone will reenter poverty by a third.

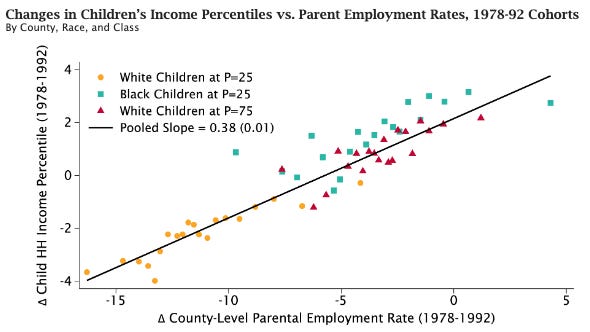

Children who are exposed to work at a young age also experience greater wage growth. A 2024 study by Chetty et al. found that the gap between the persistence of poverty of white children and black children fell by 72%, largely because parental employment rates increased in Black communities while employment fell in low-income white communities. These shifts in mobility were not explained by wealth, education, or marriage but instead by changes in the employment rate of parents. Chetty et al also finds that employment has positive spillover effects – children’s outcomes were best when other parents in their community were employed.

Creating attachments to the labor force and having parents who work is one of the most effective ways to improve social mobility. As it is, our welfare system is not designed to boost social mobility. While child poverty has indeed declined over the past several decades, social mobility has stagnated. Many children are no better off than their parents. Creating a new welfare system based on parents not working will do little to make children better off.

More Money Does Not Equal More Babies

The U.S. fertility rate is a mere 1.66 – far below the replacement rate of 2.1 needed to sustain the population. Similar patterns are emerging across the world. Subsidies for families with children, like the CTC and baby bonds, have been proposed as one way to mitigate these declines and have been tried in many countries.

But these cash transfers do little to actually boost fertility in the long term. While some countries like Hungary have seen moderate boosts in their fertility rate following increased cash transfers, they have not been sustained.

The spike in fertility rates following cash interventions likely isn’t families who thought they couldn’t afford children changing their minds or families who said they would never have kids changing their hearts. Instead, the spike is likely caused by families who were planning to have children in the future deciding to have their first or higher-order birth earlier than planned to take advantage of generous pro-natal policies. This is why most cash transfer interventions see a quick spike in fertility rates and then birth rates quickly downturn towards the baseline.

A review of experimental or quasi-experimental designs finds just that. Birth rates increased in the short term following pro-natal interventions, but the long-term was totally unaffected.

The Fiscal Reality

Setting aside that cash transfers do little to reduce child poverty, there is also the glaring reality that the U.S. cannot afford another entitlement program.

Making the expanded child tax credit from the ARP permanent would cost nearly $1.6 trillion (inclusive of the current cost of the CTC). But if the expansion under the ARP was made permanent, the CTC would be smaller than the one proposed in the Warnock-Bennet plan – meaning that the cost of their plan would be even higher.

Baby bonds aren’t any less expensive. Proposals to create baby bonds range in cost from $60 billion to $82 billion. However, these estimates are from 2019. Adjusting for inflation, those numbers would likely be closer to between $75 billion and $102 billion. For comparison, the baby bond program in Connecticut cost the Constitution state $381 million.

All of this spending will only worsen our fiscal situation, pushing inflation up and putting more strain on the Federal Reserve. Families, especially single parent households, feel a unique amount of pressure from Washington’s fiscal recklessness. What’s more, inflation is a regressive tax. Lower- and middle-income households disproportionately shoulder the burden of inflation. Creating new spending programs to help palliate the effects of Congress’ spending addiction is terribly cyclical.

Expanding the CTC also reduces the number of households with tax liability. The expanded credit contributed significantly to increasing the number of households with little or no-income tax liability. 74 million tax filers (48.3%) of all filers in 2021 had no liability. If the number of nonpayers continues to grow, our tax system will be unsustainable.

We Can Do Better

Policies aimed at making family life more affordable for families are well-intentioned, but doing so through more spending will only reduce social mobility and increase the costs of goods families rely on.

Policymakers should be more creative when it comes to pro-family policies. If the goal is to reduce the cost of goods, policymakers should reduce regulations on baby formula and roll back tariffs on food. If the goal is increased fertility, policymakers should relax zoning codes.1 If the goal is setting babies up for success, policymakers should create Universal Savings Accounts.

The problem is that these policies take more work than Washington is willing to do. Expanding the CTC is a quick political win but at the cost of true social mobility. The IRS is not a social-service agency and treating it as such fails families.