What the American Colonies Teach us About Tax Competition

Why Decentralized Tax Policy Fostered Freedom

Guest Post by Dr. Caleb Petitt

Politicians are generally resistant to dealing with tax competition, which is why the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has made a push in recent years to impose global minimum corporate taxes. Some American politicians are open to the arguments in favor of establishing tax harmonization to limit tax competition. However, the history of tax competition in the American colonies demonstrated the folly of joining the OECD’s efforts for tax harmonization.

The American colonies operated under a system of intense tax competition, and that tax competition constantly put downward pressure on tax levels in the various American colonies. Tax competition in the colonies limited the size and scope of governments which in turn prepared the colonies for a liberal, limited government in the new United States of America.

Colonial lawmakers kept taxes in their colony as low as possible to encourage migration to their respective colonies. From the founding of the colonies onward low taxes were used to attract migrants to the colonies. Every colonial charter except for Pennsylvania contained tax exemptions to encourage migration to the colony.1 The exemptions typically lasted seven to ten years from the colony’s founding, applied to everyone in the colony, and exempted the colonists from trade and/or land taxes. Although Pennsylvania did not have specific tax exemptions named in its charter, it quickly gained the reputation as a colony with cheap land and low taxes.2

The system of tax competition was not planned in the American colonies. The English government did not decide to establish a system of tax competition; rather, it developed largely as a result of the imperial strategy that England took because of the fiscal limitations of the state at the time. They engaged in contractual imperialism, which is when a state engages in colonial ventures through private agents by granting those agents charters outlining the scope of the imperial venture, the rights of the agent, and the relationship between the agent and the government. The English government granted charters to a variety of agents, which created distinct political jurisdictions in America that could compete with one another.

Tax competition is the default setting for independent political jurisdictions. The lack of enforced tax harmonization does not mean that lawmakers necessarily engage in tax competition. Lawmakers could ignore the pressures of tax competition and accept lower population growth or capital migration to their jurisdiction in order to raise tax rates.

Tax harmonization – or suppression of tax competition – on the other hand, requires deliberate planning. Lawmakers can suppress tax competition by restricting capital or labor mobility. Restrictions on capital or labor mobility limit the effects of tax competition by preventing other jurisdictions from enticing capital or labor to move out to take advantage of lower taxes in another jurisdiction. Tax harmonization is a deliberate effort taken by multiple jurisdictions to coordinate their tax rates so they can raise tax rates without suffering capital or labor flight. Colonial lawmakers chose to engage in tax competition instead of instituting illiberal barriers to restrain competition because they knew that competition helped them to continually attract new migrants to settle in their colonies.

Tax competition in the American colonies kept levels of per capita taxation extremely low throughout the colonial period. At some points in colonial history, colonial governments were able to go years without collecting taxes because they were able to fund their governments from the interest of their colonial land bank.

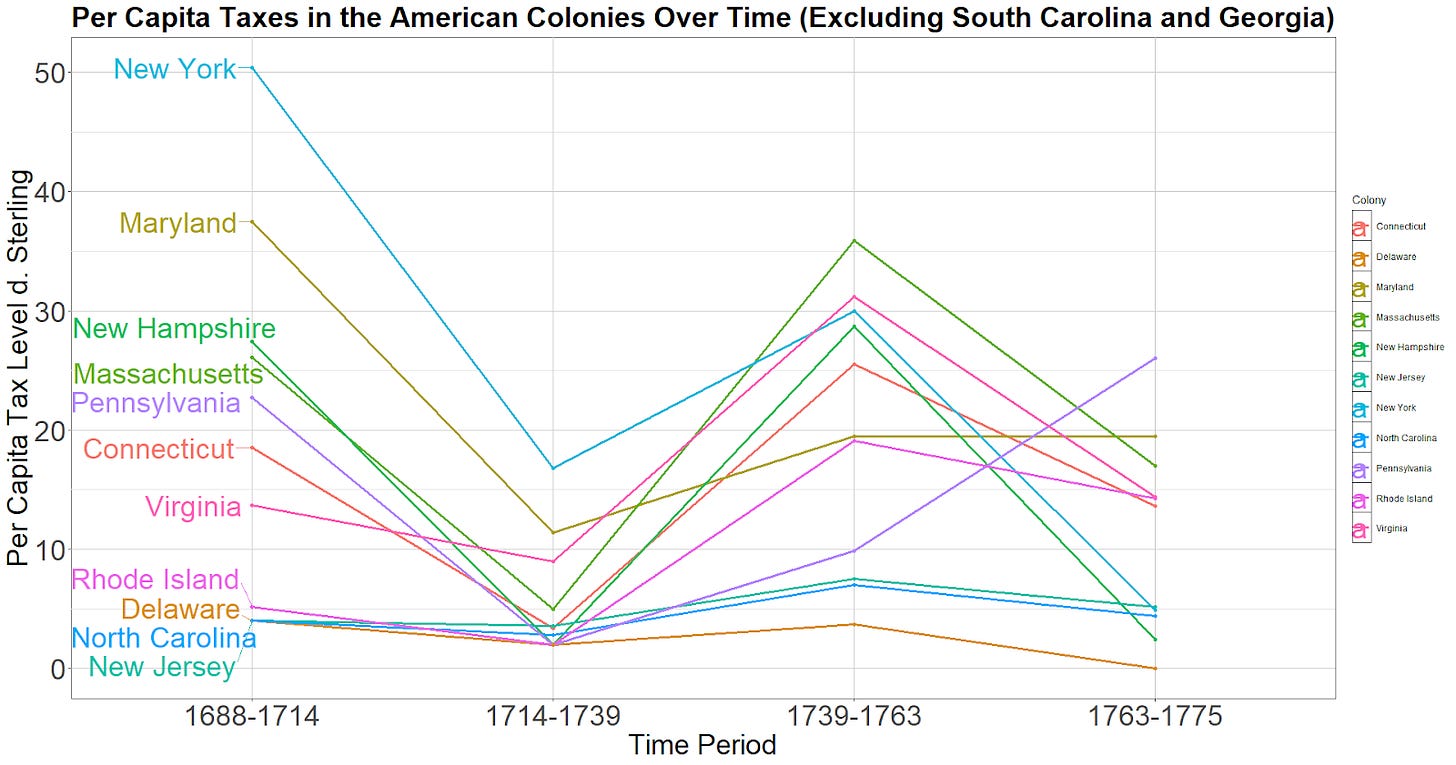

Figure 1 shows average per capita taxes in the American colonies from 1688-1714. Georgia is dropped because it does not exist for the first period and it does not collect taxes for the second and third period because it was a charity colony funded by the British government, and South Carolina is dropped as an outlier for its high taxes in the 1739-1763 period.

Figure 1 shows the changes in average per taxation in the colonies over four time periods in colonial history. The first and third periods were periods with widespread warfare and the second and fourth periods were generally peaceful. There is a clear downward trend in the data, and colonial provincial taxation stays remarkably low.

For the colonies included in Figure 1, the average colonist paid 13.8 pence annually in taxes, which was approximately 0.6% of their annual incomes. The average person in Britain paid about 10% of their annual incomes in taxes, so the colonists were nearly paying one twentieth of the taxes their British cousins were paying.

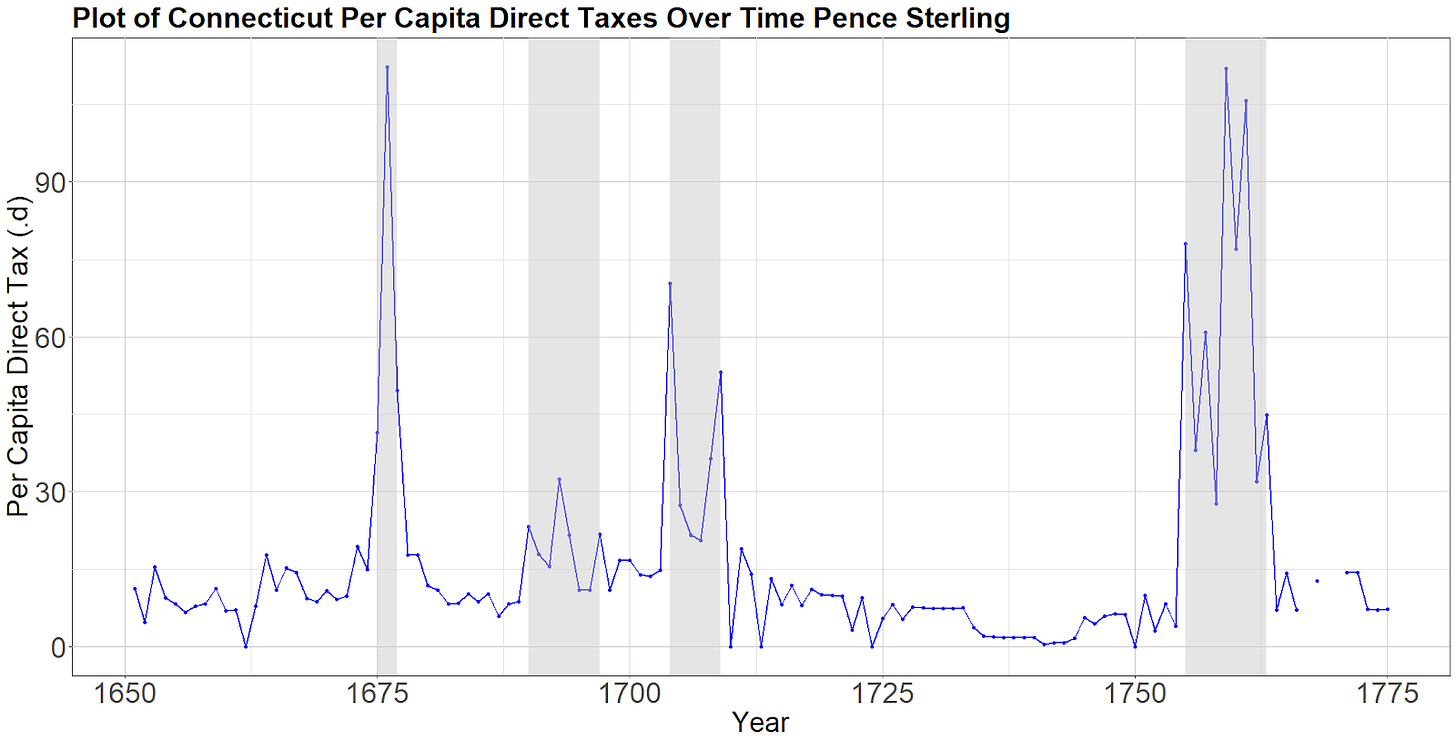

Unfortunately, the data are not granular enough to do a more detailed analysis for all the colonies. However, Connecticut has very detailed records of its direct tax revenues. Figure 2 shows annual per capita direct taxes (pence sterling) from 1651-1775, with war years highlighted.

Defense was the primary public good provided by colonial governments, so going to war dramatically increased the taxes that a colonial government had to raise. However, as Figure 2 shows, once the war was over, tax collection dropped precipitously back to its pre-war level. There was little to no lag in reducing taxes after peace was established, and taxes dropped all the way back down to their previous low level, so there were no ratchet effects.

Figure 2 clearly shows that peacetime per capita taxation in Connecticut was stable throughout the colonial period, where the rate hovered around 10 d. per person, with a high peacetime average of 14.5 d. and a low peacetime average of 5.9. The average per capita tax rate for the last decade of Connecticut as a colony was only 0.1 d. lower than the average from the first 24 years of peacetime data available.

Tax competition kept taxes remarkably low throughout the colonial period, which fostered a love of liberty and limited government in the American colonists. The colonists became extremely sensitive to encroachments on their liberty, so they reacted strongly against attempts by the British government to tax their trade, which led to the American Revolution.

Love of liberty, acceptance of competition, and distrust of big government goes back to America’s roots, and we should strive to live up to the example set by the American revolutionaries as we celebrate the 250th anniversary of the outbreak of the American Revolution this year.

Dr. Caleb Petitt is a Research Associate at the Independent Institute. He recently completed his PhD in Economics from George Mason University

Alvin Rabushka, Taxation in Colonial America. (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2015)

Rabushka